“Love is stronger than life. It reaches beyond the dark shadow of death.” –Clifton Webb as Waldo Lydecker in Laura (1944)

The story of romance between Laura Hunt (Gene Tierney) and Det. Lt. Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews) is far from ordinary. Unlike the lighthearted affairs that initiate many a love story, Laura (1944), a hybrid of film noir and romance, begins with murder. The plot twists and turns past the usual matrimonial knot. All the while, Otto Preminger masterfully unravels the haunting tale of Laura to the tune of David Raskin’s melancholy score, and envelops it in the shadows of Joseph LaShelle’s cinematography.

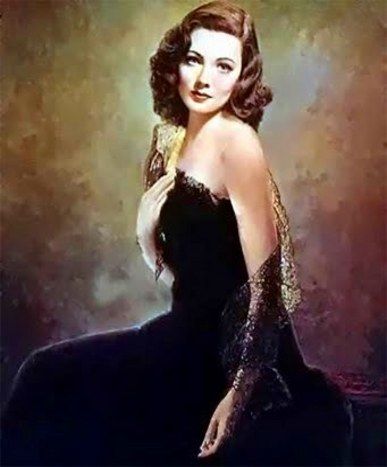

While McPherson’s work with the New York City Police Department leads him to investigate the murder of a glamorous and successful advertising executive, he suddenly finds himself falling in love with the absent Laura. Unable to romance Laura in person, McPherson is limited to discovering stories about Laura in order to rebuild a more tangible trace of her and to solve the story of her murder. As the plot unfolds, one item beckons to McPherson and to the viewer constantly. The item in question is a portrait of Laura—quite literally, the object of his affection.

Bewitched by the portrait, McPherson is all the more intrigued to pursue the story of Laura and her demise. Though she is not present physically for a fair portion of the film, her presence looms heavily. Like McPherson, the portrait—a large, poster painted photograph of Tierney—is one of the few lanterns in the fog that helps viewers see Laura. This portrait becomes an aching symbol of loss and the source of many questions for McPherson and the viewer. To further the eeriness of the portrait, McPherson finds that the Laura he sees in the portrait would certainly no longer look like the physical Laura. The beautiful woman in the portrait was supposedly murdered and marred by a shot to the face—just inside the doorway of the apartment where McPherson so frequently stands.

Interestingly, it is the portrait that soundlessly speaks to McPherson more than any other witness accounts. McPherson and the portrait watch the plot unfold before their eyes, with the portrait almost taking on the persona of a quiet witness in its own right. Though the portrait is the clearest remnant of a presumably dead Laura, her likely death does not stop McPherson’s interest in her from growing into a relentless passion.

After interviewing Laura’s mentor, Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb); her playboy fiancé, Shelby Carpenter (Vincent Price); and her loyal housekeeper, Bessie Clary (Dorothy Adams), McPherson soon becomes obsessed with Laura. He pours over her letters and diary to the point of Lydecker accusing him of falling in love with the deceased Laura.

Once callous and dead to emotion, it is the portrait that awakens feelings in McPherson. As he works through her case, he begins exhibiting hints of shame and heartbreak. His bid on the portrait is no surprise to the viewer; it is the portrait that subtly romances him in Laura’s physical absence.

When Laura herself walks into the apartment, the ghost of Laura that McPherson has fashioned dissipates in an effort to give way to the truth, for better or worse. With Laura alive, who is the real victim? Will the real Laura match up to the dreamy vision McPherson has pieced together?

As Laura appears to appear increasingly guilty in person, McPherson works to counter his attraction to her, worrying that the physical manifestation of his assumed Laura is at odds with the real one. Suddenly, the portrait seems to be breathing before his eyes with a story to tell. Now, more than ever, it is McPherson who must observe carefully and act tactfully. However, thanks to McPherson’s relationship with the portrait, the viewer can believe that he and Laura already know each other in a sense. Because of this unspoken understanding, the viewer can begin to believe that McPherson has a chance at solving this case.

In both Vera Caspary’s novel, Laura, and the film, Laura is true, independent, beautiful, and intelligent. Her previous suitors prove to be no match for her and cause her to be viewed with suspicion.

Despite the seriousness of the investigations, Laura maintains a sense of integrity throughout the story, while other characters—male and female—do not. Her only possible equal arrives in the form of McPherson, who investigates her murder; investigates her for murder; and becomes a lover and savior to her in the end. Unlike romance novels of the day, it is clear that Laura is not a helpless, virginal character; rather, she is a woman with a strong career and sexual history who will attach herself to an unfit man in order to fulfill her dreams of exploring a domestic life.

In the end, the two lovers differ from usual romances once again, as they never share a kiss. Rather, McPherson pulls her into his arms in an effort to save her life, as her would-be murderer falls dead. As the camera pans to the broken clock, both McPherson and the viewer know that they are no longer limited to the mystifying portrait of a presumably dead Laura. Instead, McPherson’s dream Laura and the real Laura are masterfully woven together through the death of a character who threatened her murder, conclusively bringing life to Laura and new romance as the credits roll.

I saw this movie in a theater when it first came out and was mystified with it. I have seen it several times one TCM since and enjoy it each time.

Pingback: Lead Her to Heaven (1945) | Hometowns to Hollywood

Pingback: The Uninvited (1944) | Hometowns to Hollywood