Charlie Allnut: How’d you like it?

Rose Sayer: Like it?

Charlie Allnut: White water rapids!

Rose Sayer: I never dreamed…

Charlie Allnut: I don’t blame you for being scared – not one bit. Nobody with good sense ain’t scared of white water…

Rose Sayer: I never dreamed that any mere physical experience could be so stimulating!

–The African Queen (1951)

The African Queen (1951) offers a fascinating story both on-screen and, in terms of its production, an intriguing off-screen journey. The film is an adaptation of a novel by the same name published in 1935 by C.S. Forester. The film iteration of this tale was directed by John Huston with a screenplay by Huston, James Agee, Pieter Viertel, and John Collier. It was produced by Sam Spiegel and John Woolf, starring Humphrey Bogart, Katharine Hepburn, and Robert Morley, with cinematography by Jack Cardiff.

The African Queen is set in World War I East Africa, telling the tale of Canadian riverboat captain Charlie Allnut (Bogart) and his adventures with English missionary Rose Sayer (Hepburn), who persuades him to take his boat–The African Queen–up a dangerous river to attack a German gunship. They are absolute opposites to one another, to the point of both frustration and comedy. Their stories intertwine due to tragedy and war and, as the film progresses, they find themselves forming an unlikely but captivating bond.

The cast for this film is as follows:

- Humphrey Bogart as Charlie Allnut

- Katharine Hepburn as Rose Sayer

- Robert Morley as Reverend Samuel Sayer, “The Brother”

- Peter Bull as the Captain of the Königin Luise

- Theodore Bikel as the First Officer of the Königin Luise

- Walter Gotell as the Second Officer of the Königin Luise

- Peter Swanwick as the First Officer of Fort Shona

- Richard Marner as the Second Officer of Fort Shona

- Gerald Onn as Petty Officer of the Königin Luise (uncredited)

Hepburn and Bogart command the camera as iconic talents with passionate, energetic performances and gripping on-screen chemistry. The film is beautifully shot and offers its fair share of edge-of-your-seat drama as well as lighter comedic moments.

Behind the scenes, the production ran into issues with the censors, particularly in the case of two unmarried characters living on the boat. The production was financed by Romulus Films and Horizon Pictures, and distributed by United Artists.

The female lead was originally offered to Bette Davis in 1938, with David Niven as Charlie. It was offered to Davis again in 1947, with James Mason, as Charlie, but she had to drop out due to pregnancy. By the time Davis tried out for the role again in 1949, plans were underway for Hepburn to star.

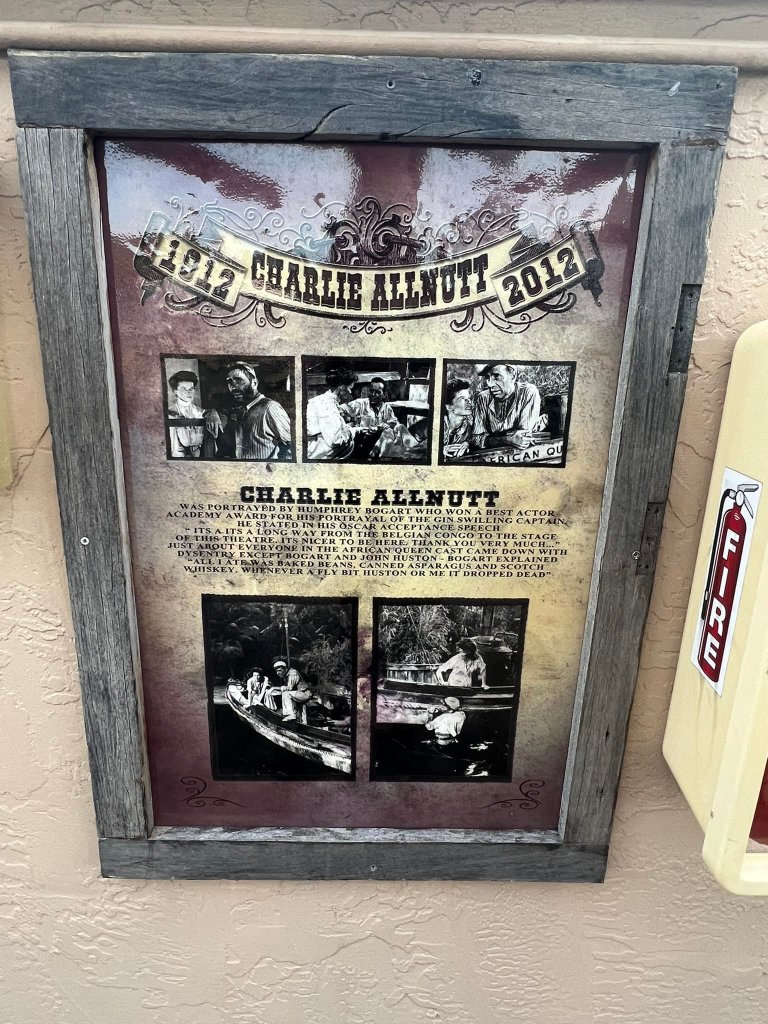

The majority of the film was shot on location in Uganda and the Congo in Africa, posing its fair share of challenges in transporting large three-strip Technicolor cameras in additio to the cast and crew frequentlhy falling ill. In fact, Hepburn kept a bucket off-screen during her character’s organ-playing sequences. Bogart said that, “All I ate was baked beans, canned asparagus, and Scotch whiskey. Whenever a fly bit Huston or me, it dropped dead.” Hoston and Bogart claimed to evade illness by basically living on Scotch whiskey.

The remainder of the film was shot in the UK. In particular, scenes in which Hepburn and Bogart are in the water were shot in the safety of sutdio tanks at Worton Hall Studios in Isleworth.

Additionally, scenes on the boat were filmed by using a large raft with a rough reproduction of a portion of the boat on top. Other areas in the boat set could be removed to make room for Technicolor cameras. Due to the potential dangers of shooting the rapids scenes with the full-sized boat, a small-scale model was used in the London studio tank. Similarly, Bogart and Hepburn are replaced with dummies in the majority of sequences in which their characters are shown aboard the boat at a distance.

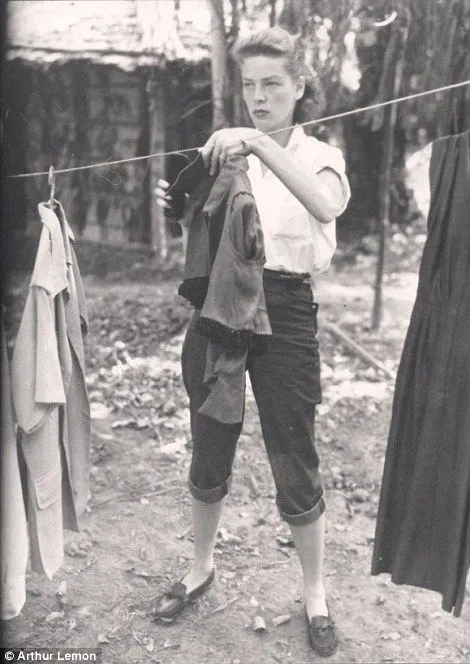

Sources claimed that everyone in the cast and crew got sick except Bogart and Huston, who said they avoided illness by essentially living on imported Scotch whiskey. Bogart later said, “All I ate was baked beans, canned asparagus and Scotch whiskey. Whenever a fly bit Huston or me, it dropped dead.” Lauren Bacall famously ventured along for the filming in Africa to be with husband Bogart. She played den mother during the trip, making camp and cooking. This also marked the beginning of her life-long friendship with Hepburn. Bacall also played nursemaid to the cast and crew whenever anyone got sick, which was often. There was dysentery, malaria, and bites from all sorts of bugs to deal with. One night, a crew member even came down with appendicitis. Bacall saved the day by being the only one who had thought to bring antibiotics, which were given to the man before he was rushed to the closest hospital in Stanleyville for emergency surgery.

Bogart hated Africa immediately and was miserable, but Hepburn adored it, calling it “utterly divine.” Bogie complained about everything: the heat, the humidity, the dangers, the food. He recalled, “While I was griping, Katie was in her glory. She couldn’t pass a fern or berry without wanting to know its pedigree, and insisted on getting the Latin name for everything she saw walking, swimming, flying or crawling. I wanted to cut our ten-week schedule, but the way she was wallowing in the stinking hole, we’d be there for years.”

Shooting was slow going. Tempers often flared and the cast and crew faced constant dangers and difficulties including torrential rains that would close down shooting, wild animals, venomous snakes and scorpions, crocodiles, armies of ants, water so contaminated that they couldn’t even brush their teeth with it, and food that was less than appetizing. Bacall recalled, “We decided first night out that it was advisable not to ask what we were eating, we didn’t want to know.”

There was a language barrier between the film people and the locals that led to wild misunderstandings. For instance, for the scene that called for Brother Samuel’s mission to be burned by the Germans, the crew built a village for the express purpose of burning it down. Huston asked a local leader to bring a bunch of locals to be extras in the scene. However, when the day came for filming, not one of them showed up. It turned out that a rumor had spread among them that the film people were cannibals and it was a trap–anyone who came would be eaten.

The boat used as The African Queen was built in England in 1912 and used by the British East Africa Company from 1912-68 to shuttle passengers and cargo across Lake Albert (on the border between Uganda and Belgian Congo). The African Queen sank and had to be raised twice during filming of the movie. Bacall is quoted as saying, “The natives had been told to watch it and they did. They watched it sink.”

The film opened on December 26, 1951, at the Fox Wilshire Theatre in Beverly Hills. Bogart won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in this movie, making him the last man born in the 19th century to ever win a leading role Oscar.

The African Queen maintains an interesting legacy today. Although the live action Disney film Jungle Cruise (2021) was based on a Disneyland ride, the visual aesthetic and photography of that film drew heavily on The African Queen. Even Dwayne Johnson’s clothing in the Disney film is similar in style to Bogart’s. The African Queen was one of Walt Disney’s favourite movies and he is on record as saying he wished it had been made by him.

Hepburn also wrote about her experiences making The African Queen in The Making of the African Queen or How I went to Africa with Bogart, Bacall and Huston and almost lost my mind.

Most excitingly, The African Queen was actually the L.S. Livingston, which had been a working diesel boat for 40 years. The steam engine was a prop, and the real diesel engine was hidden under stacked crates of gin and other cargo. At one time it was owned by actor Fess Parker and toured the world as part of various exhibitions. The boat was restored in April 2012 and is docked next to the Holiday Inn in Key Largo, Florida. Individuals may book a voyage aboard The African Queen.

I was lucky to take this fabulous tour in January 2023. The boat fits few passengers–there were six people aboard the boat in total on my tour–and this makes for a lovely ride. The captain arrived prepared with a binder of photos to tell the story of the boat, the production of the film, and the boat’s restoration. As we went out to sea, the captain kept us entertained with stories as well as a movie trivia game (which I shamelessly won, ha!).

The captain came ready with empty bottles for us to use as photo props, commemorating a specific movie moment. To my shock, no one was taking him up on the photo opportunities, but I was more than ready to take advantage of them.

Now, here comes the moment of a LIFETIME. The captain offered us a chance to actually operate The African Queen. Again, to my shock, no one else wanted to! So, most definitely did. What I seriously did not expect was to have her under my control the entire time we were out of the no wake zone!

All in all, this was a MAJOR and unexpected dream come true that made my classic film-loving heart SING. I couldn’t help but remember Rosie’s epiphananous moment in the film during which she says, “I never dreamed that any mere physical experience could be so stimulating!” I highly recommend this tour to any classic film fan and to participate in it as fully as possible.