“I’m an incurable optimist and a go-getter – it’s in my nature to focus much more on what makes me happy than what makes me nervous.” –Colleen Moore

Kathleen Morrison, later known as Colleen Moore, was born in Port Huron, Michigan, to Charles and Agnes Kelly Morrison on August 19, 1899. Moore’s family moved frequently, residing in cities like Hillsdale, Michigan; Atlanta, Georgia; Warren, Pennsylvania; and Tampa, Florida. Additionally, her family typically spent summers in Chicago, where Moore’s Aunt Lib and Uncle Walter Howey lived. Howey, in particular, was well connected, as he was the managing editor of the Chicago Examiner, owned by William Randolph Hearst.

At age 15, Moore already had dreams of starring in films. Moore kept a scrapbook where she would paste pictures of her favorite actors after clipping them from motion picture magazines. However, Moore kept a page blank, reserved for when she would one day become a star. Reportedly, she and her brother began their own stock company, performing on a stage created from a piano packing crate. Incidentally, Chicago’s Essanay Studios was located near the Howey residence. Moore appeared in the background of several Essanay films, typically as a face in a crowd. Since film producer D.W. Griffith was in debt to Howey for helping him get both The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916) through the Chicago censorship board, he secured a screen test for Moore. Her contract with Griffith’s Triangle-Fine Arts was conditional, as Moore possessed one brown eye and one blue eye. Her eyes photographed favorably, so Moore left for Hollywood with her grandmother and mother as chaperones and began her film career.

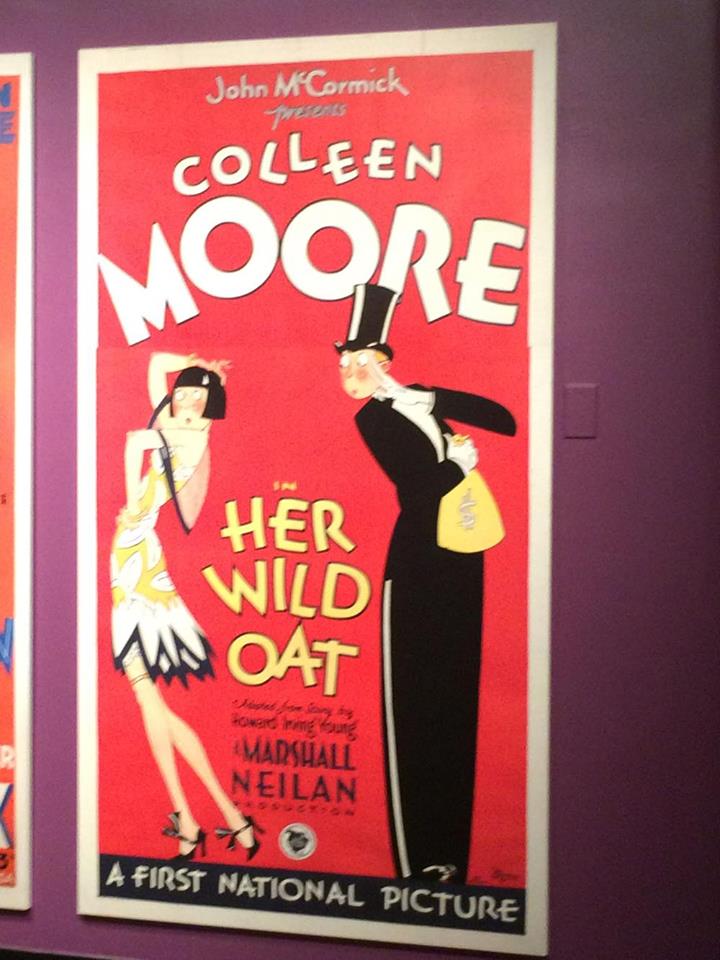

Moore’s first credited role was in The Bad Boy (1917) for Triangle Arts. This appearance was followed by An Old Fashioned Young Man (1917) and Hands Up (1917), gradually allowing Moore to develop her career and become noticed and enjoyed by audiences. She later signed a contract with the Selig Polyscope Company, appearing in films like A Hoosier Romance (1918) and Little Orphant Annie (1918), leading her to become popular among moviegoers. Moore also performed with Fox Film Corporation, Ince Productions—Famous Players-Lasky, and Universal Film Manufacturing Company, before completing the next stage of her career with the Christie Film Company.

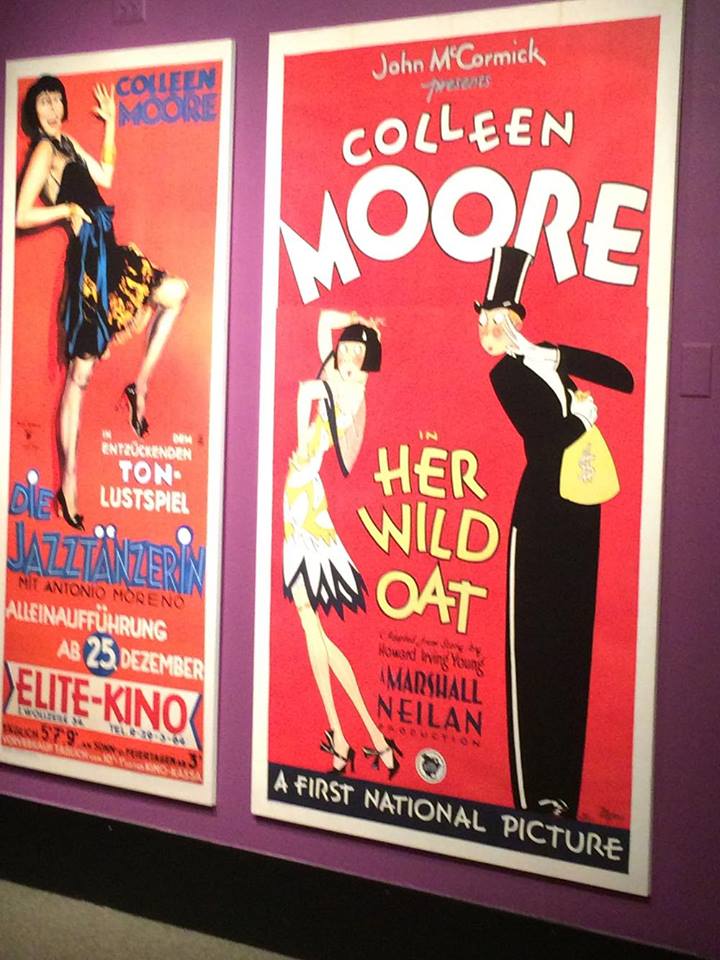

Moore was married to producer John McCormick from 1923 until their divorce in 1930.

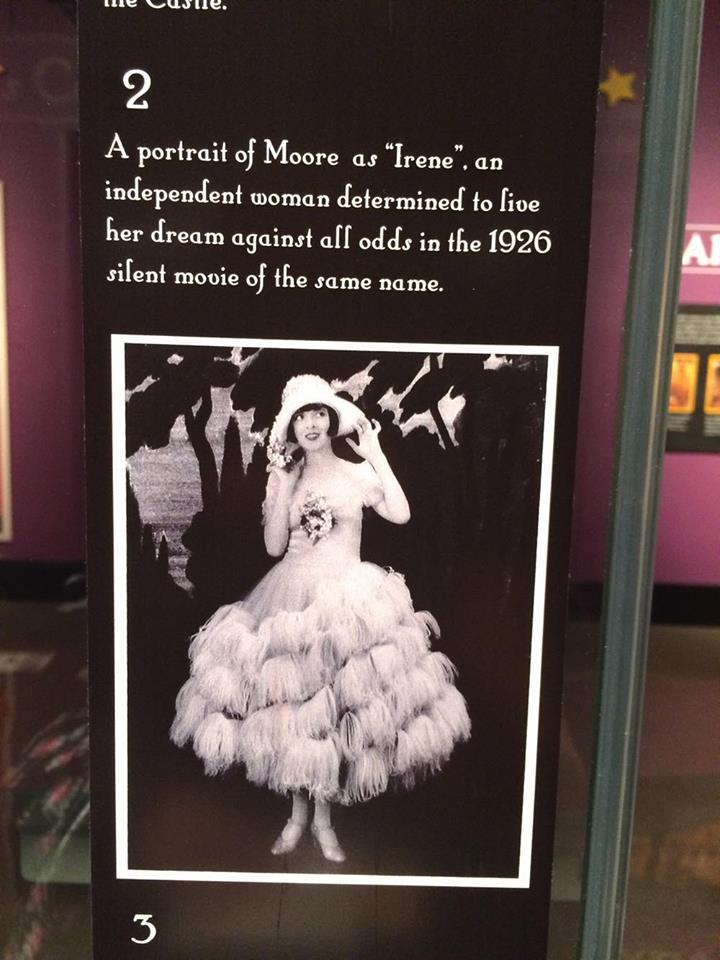

Moore starred in Flaming Youth (1923), solidifying her image as a flapper; however, Clara Bow soon became a rival to Moore with a similar image. Moore continued her film career with appearances in comedies and dramas. When Moore worked in The Desert Flower (1925), she injured her neck and spent six weeks in a bod cast. After her recovery, she finished filming and was able to leave for a publicity tour throughout Europe.

Two of Moore’s key passions were dolls and films; each of these interests would become prominent throughout her life. Though approximately half of her films are now lost, Moore is, remembered as a delightful silent film actress by film aficionados. Moore’s films would often feature her as a good girl putting on a bad girl façade, and always carrying out her roles with panache. Her aunts, however, took care to indulge her in another great passion, which is the focus of this article: dollhouses. They frequently brought her miniature furniture from their many trips, with which she furnished the first of a sequence of dollhouses.

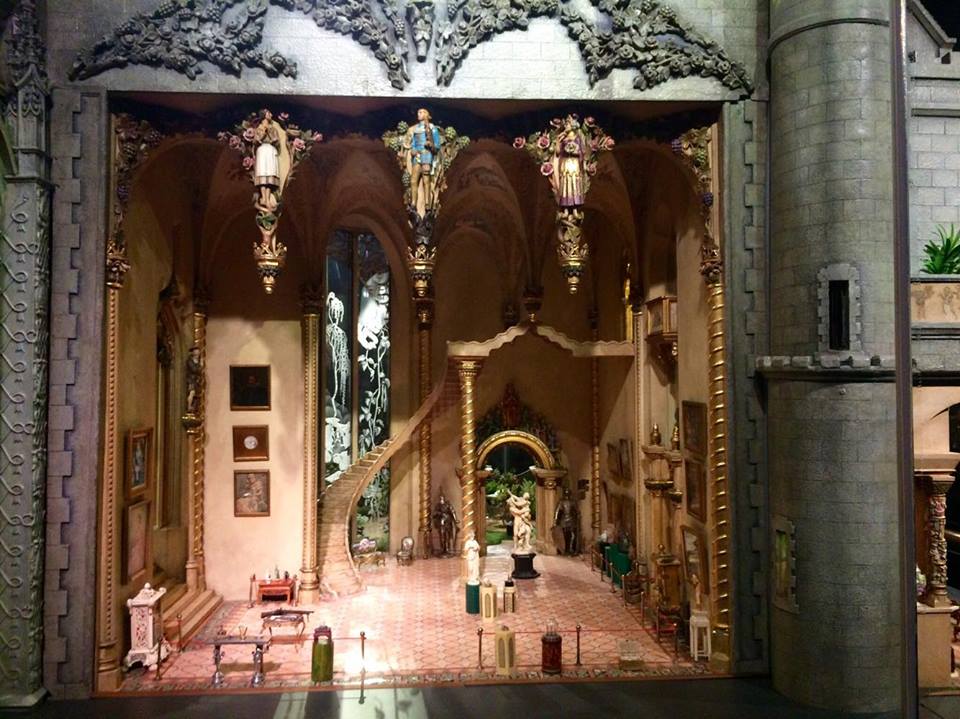

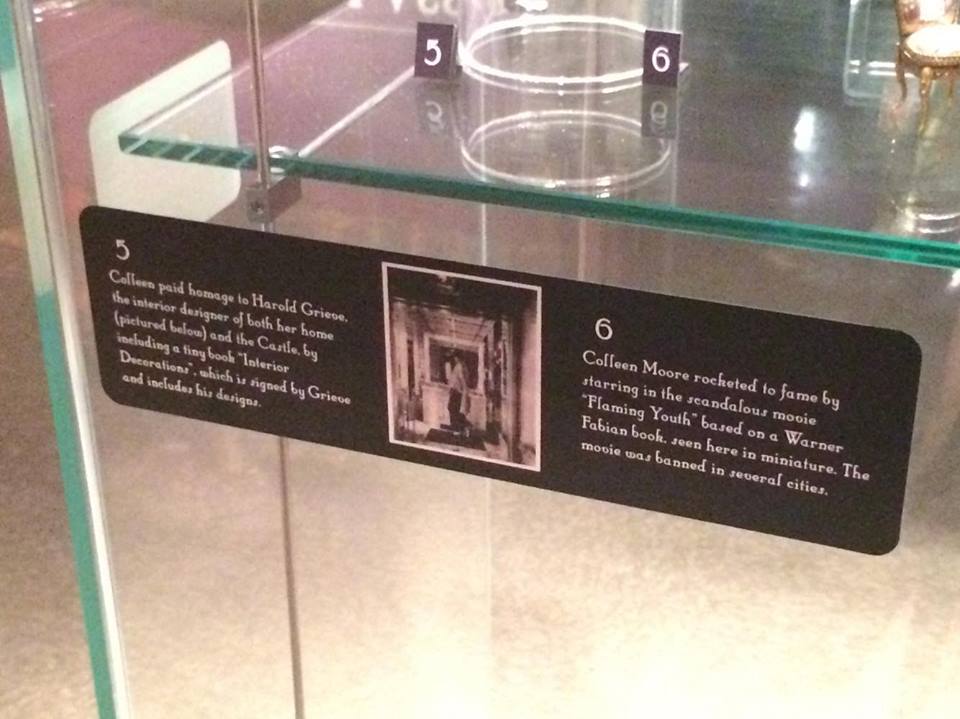

In 1928, Moore enlisted the help several professionals to help build a massive dollhouse for her growing collection of miniature furnishings. The professionals included Moore’s father as chief engineer, set designer Horace Jackson, and interior designer Harold Grieve. Cameraman Henry Freulich worked on the lighting, which was installed by an electrician. This dollhouse has an area of nine square feet, with the tallest tower standing several feet high and the entire structure weighing one ton. This eventually became known as Colleen Moore’s Fairy Castle.

By 1929, the advent of sound had taken the film industry by storm, leading Moore to take a hiatus from acting. She married stockbroker Albert P. Scott in 1932 and they resided in Bel Air together until their 1934 divorce. Moore’s final film appearance occurred in that year in The Scarlet Letter (1934).

In 1937, Moore married stockbroker Homer P. Hargrave, remaining with him until his passing in 1964. Hargrave would ultimately provide much of the funding for her dollhouse. Moore adopted Hargrave’s children, Homer and Judy, to whom she remained devoted throughout her life. In the 1960s, Moore formed a television production company with King Vidor and published two books: How Women Can Make Money in the Stock Market and Silent Star: Colleen Moore Talks About Her Hollywood. She remained a popular interview subject and frequent guest at various film festivals, discussing the silent film era.

Moore married for the last time to builder Paul Magenot. They remained together until her passing on January 25, 1988, in Paso Robles, California, from cancer. She was 88 years old.

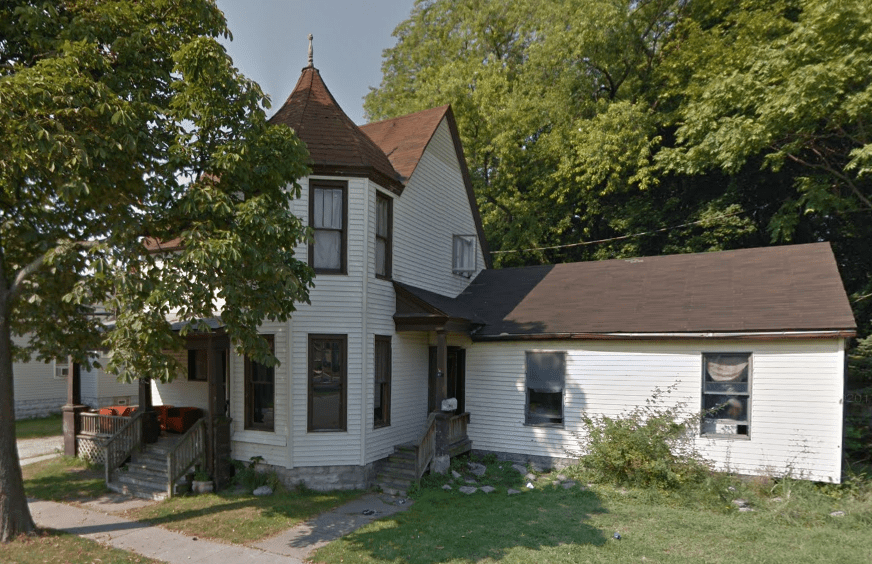

Moore’s childhood home stands at 817 Ontario St., Port Huron, Michigan.

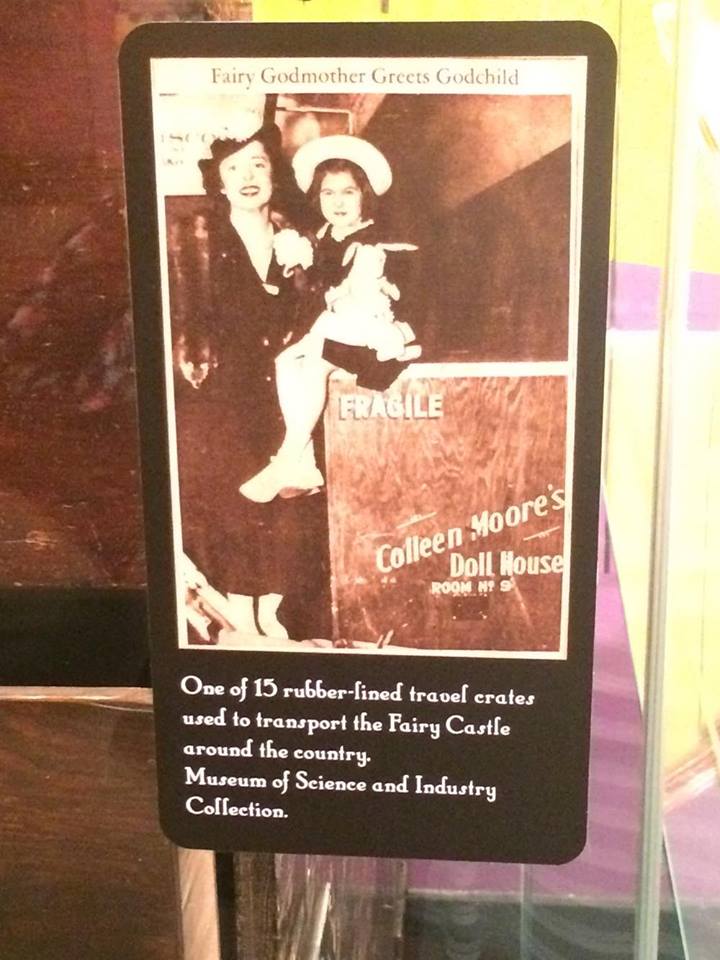

Colleen Moore’s Fairy Castle survives to this day. The dollhouse made its public debut at Macy’s in New York and traveled throughout the United States, raising approximately one half-million dollars for children’s charities. The dollhouse showcases ornate miniature furniture and art as well as the work of beyond 700 different artisans and has been a featured exhibit at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry since the 1950s.

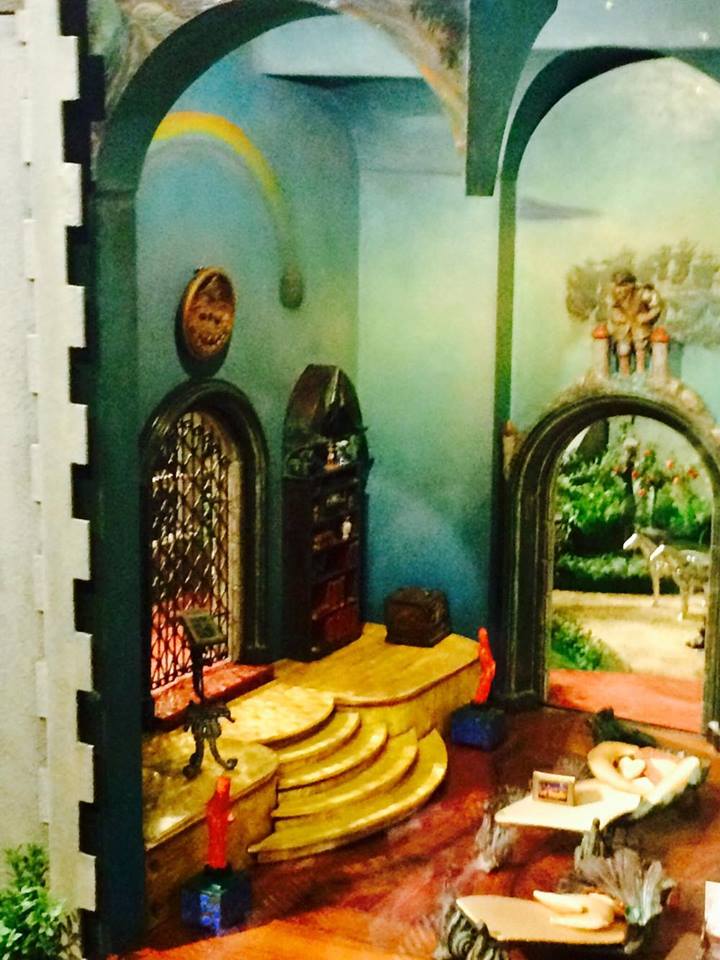

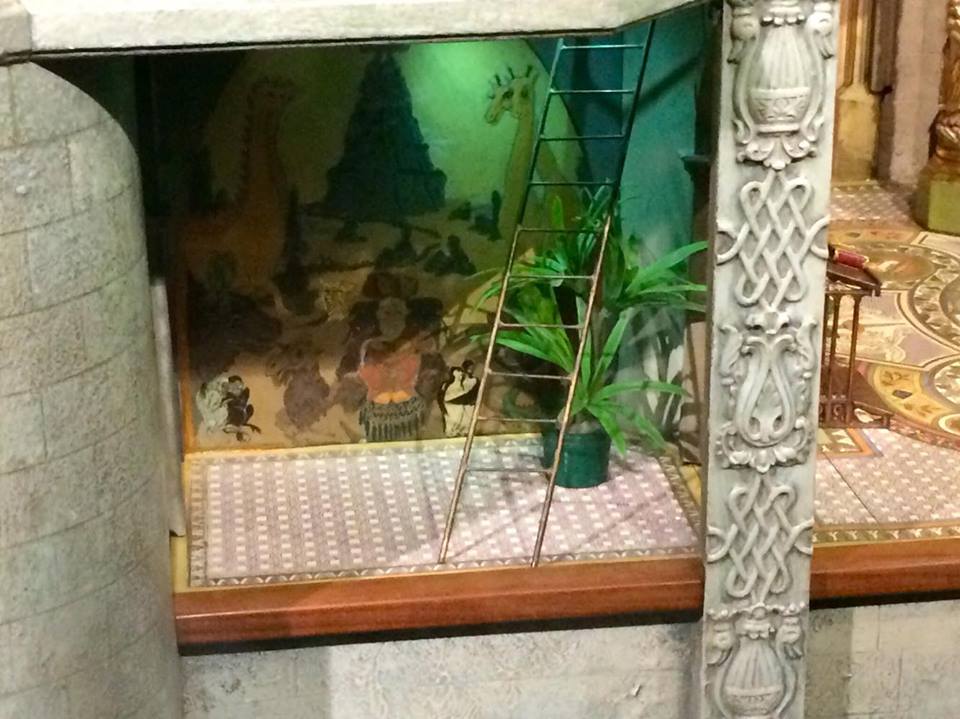

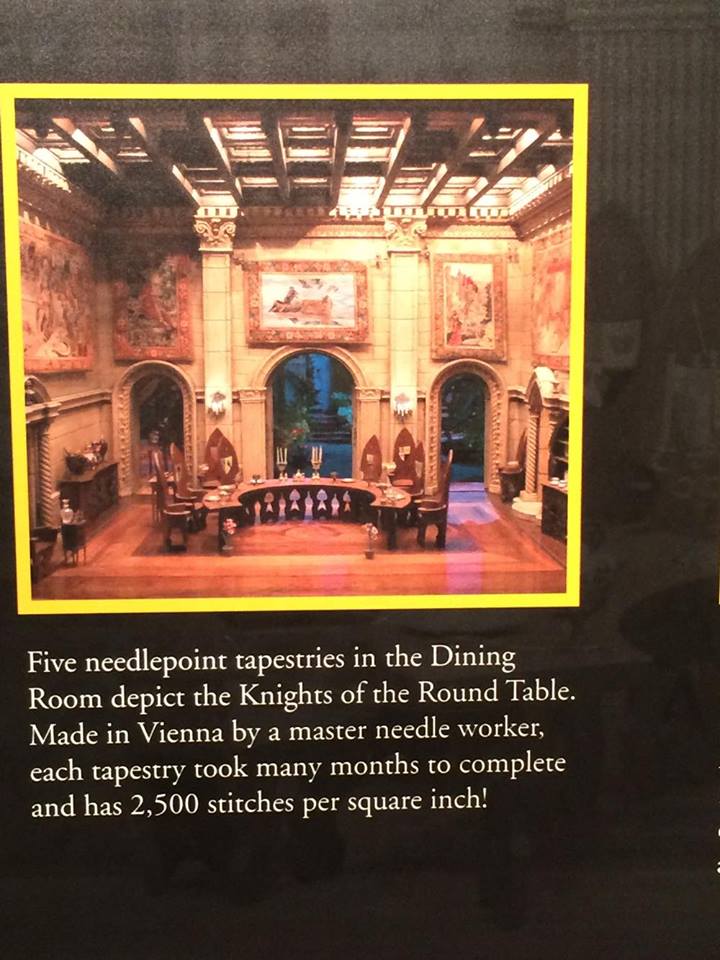

The Colleen Moore Dollhouse or “Fairy Castle” possesses thirteen key rooms, including: the Magic Garden, Library, Small Hall, Chapel, Great Hall, Drawing Room, Dining Room, and Kitchen on the first floor; Ali Baba’s cave, the Prince’s Bedroom, the Princess’ Bedroom, and Royal Bathrooms on the second floor; and an Attic on the third floor. None of the rooms have actual dolls in them; visitors are to imagine their own fantasy residents.

The Magic Garden features the rocking cradle of Rock-a-bye Baby, which is in perpetual motion. The golden cradle is bedecked with pearls made from the jewelry of Moore’s grandmother, who believed that more people would visit the dollhouse than her grave. There is also a replica of Napoleon’s carriage in the garden, which was gifted to Moore by automobile designers from Detroit. When the dollhouse first debuted, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s mother presented Moore with a gold plaque for the castle, which is still affixed to the dollhouse. The outside of the dollhouse is decorated with reliefs from stories such as The Wizard of Oz and Aesop’s Fables.

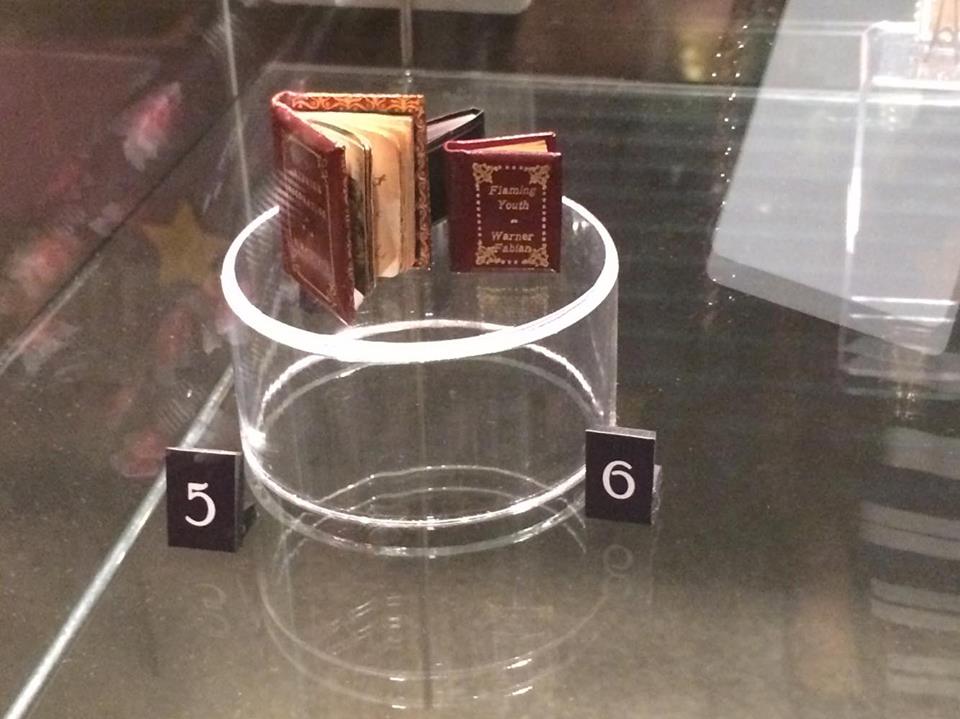

The Library is decorated with undersea motifs and features 65 miniature books from the 18th century, including a small Bible from 1840 that was presented to Moore by actor Antonio Moreno. In order to grow her collection of petite books, Moore commissioned modern printings of them. They were designed as one-inch, leather-bound squares with gold accents. Moore also invited authors of her day to sign the blank pages. She secured signatures from Edgar Rice Burroughs, Noel Coward, Arthur Conan Doyle, Edna Ferber, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Anita Loos, John Steinbeck, and many more luminaries beyond just writers. The most valuable miniature book in the house features the signatures of Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard M. Nixon.

The Small Hall links the Library and the Chapel, with a mural portraying Noah relaxing after bringing the ark to land. The Chapel features designs inspired by the Book of Kells and possesses an ivory floor. Stained glass windows, a gold altar, and a miniaturized silver throne modeled after the throne at Westminster Abbey all decorate the Chapel. Handwritten musical manuscripts from Stravinsky to Gershwin are piled near a beautiful organ with gold pipes, not far from a Russian icon detailed with emeralds and diamonds from a broach Moore purchased. A vigil light showcases a diamond from Moore’s mother’s engagement ring. Moore’s parents also gave her a small vial containing a crucifix that is over 300 years old. Playwright and congresswoman Clare Booth Luce gave Moore a gold medallion with a sliver believed to be from the true cross. A stained glass screen also stands in the Chapel, taken from Lambeth’s Palace after a World War II bombing raid.

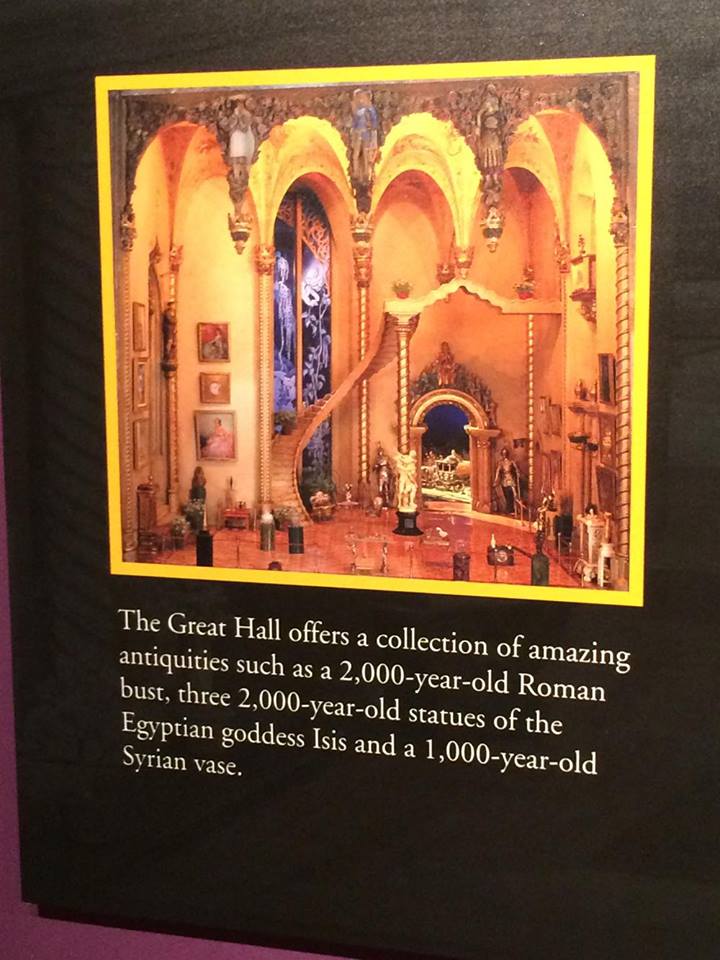

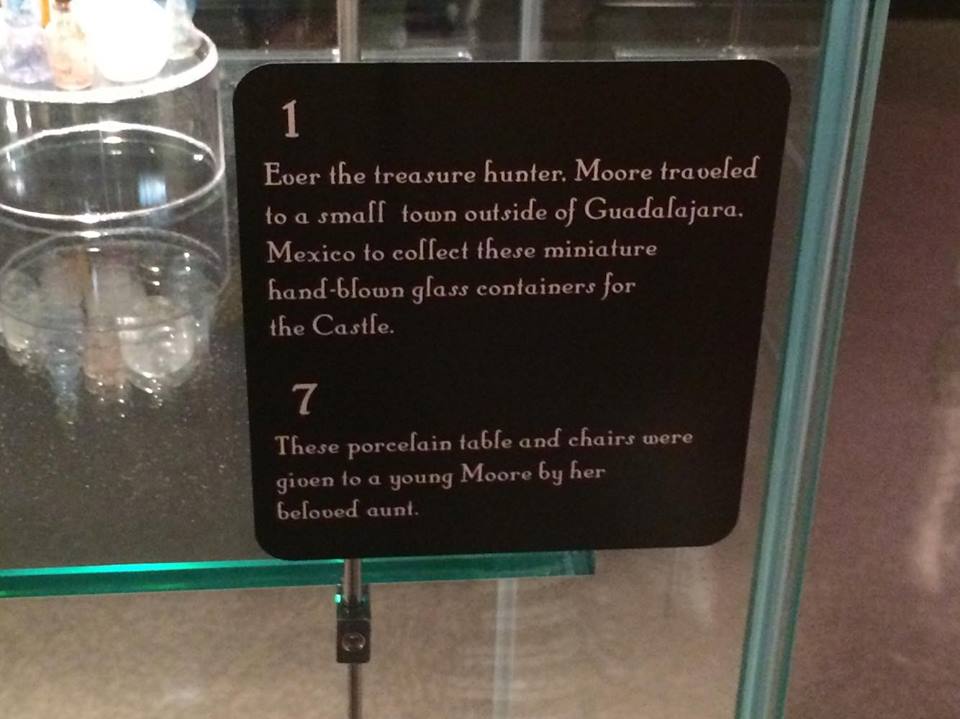

The Great Hall continues the fairytale theme of the dollhouse, featuring paintings of various fairytale and folktale characters. The Great Hall displays items from fairytales like a museum of sorts. Moore commissioned a retired glassblower to fashion Cinderella’s tiny glass slippers for the dollhouse. The Three Bears’ chairs are also showcased in the dollhouse under a glass bell to prevent them from being inhaled. All paintings in the Great Hall are miniature versions of actual works of art. Additional art decorating the Great Hall includes 2000-year-old Egyptian statues, a Roman bronze bust from the first century, and many more treasures given to Moore. Two silver and gold knights from Rudolph Valentino guard the entrance to the Great Hall.

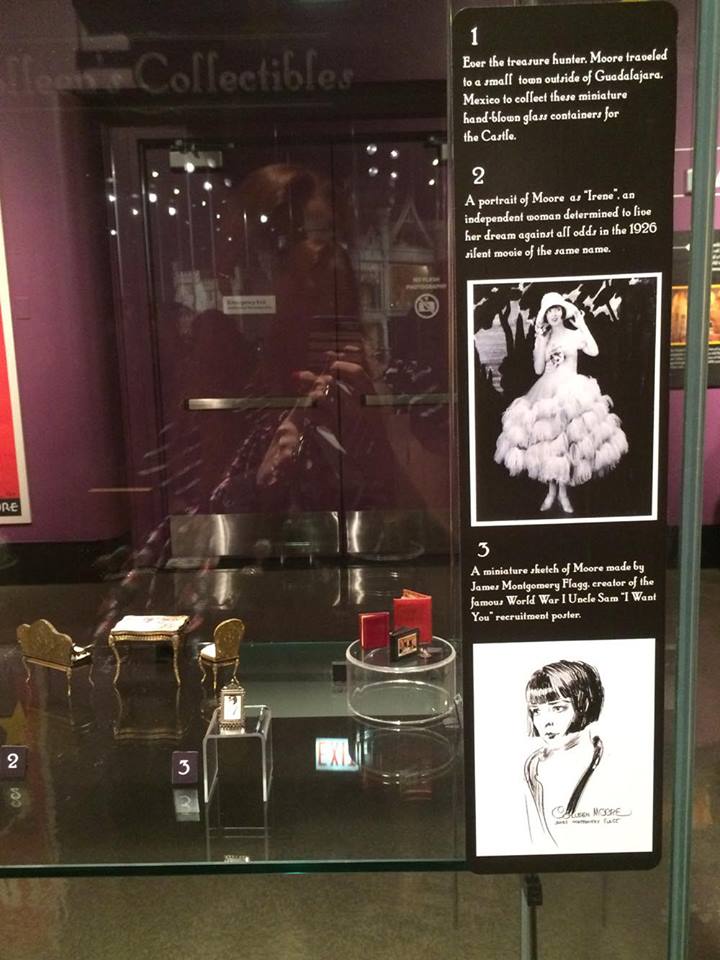

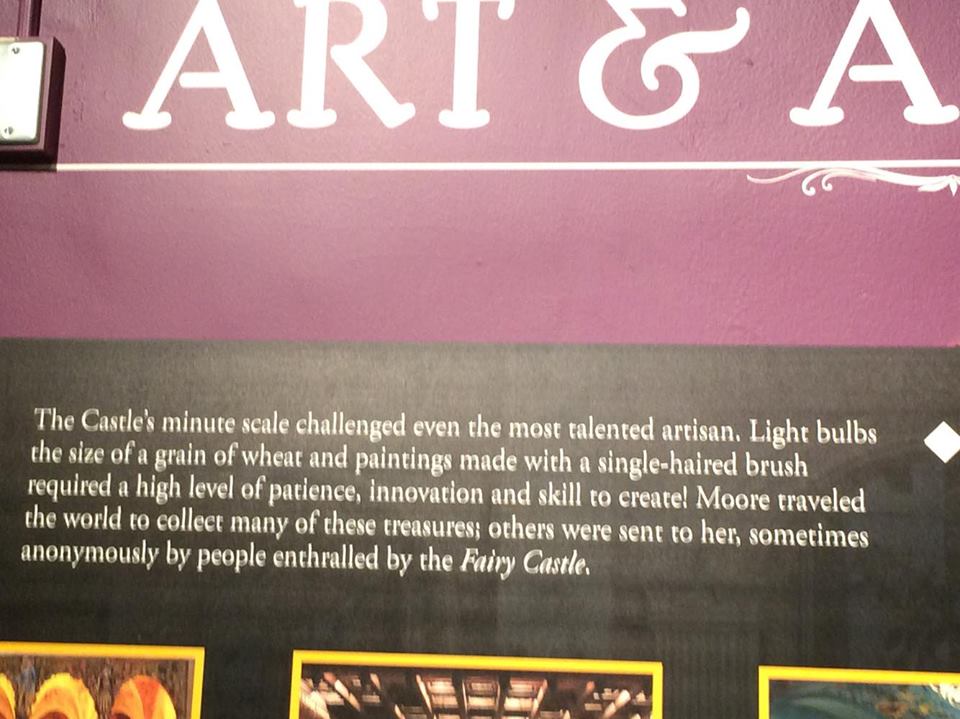

The Drawing Room contains a chandelier made from Moore’s diamond and emerald jewelry, shining over two artistic contributions: Los Angeles architect George Townsend Cole’s “Cinderella” mural and illustrator James Montgomery Flagg’s portrait of Moore. Nearby, the Dining Room possesses a medieval theme with extremely detailed miniatures. Moore’s charm bracelets were re-purposed to create a collection of gold teapots arranged on a shelf. In fact, the details on the dinnerware are so fine that many were painted with the use of a single-haired brush. The entire table service is gold, with half-inch knives bearing Moore’s initials. The Kitchen features the lone surviving piece from Moore’s first doll house: a purple wine glass.

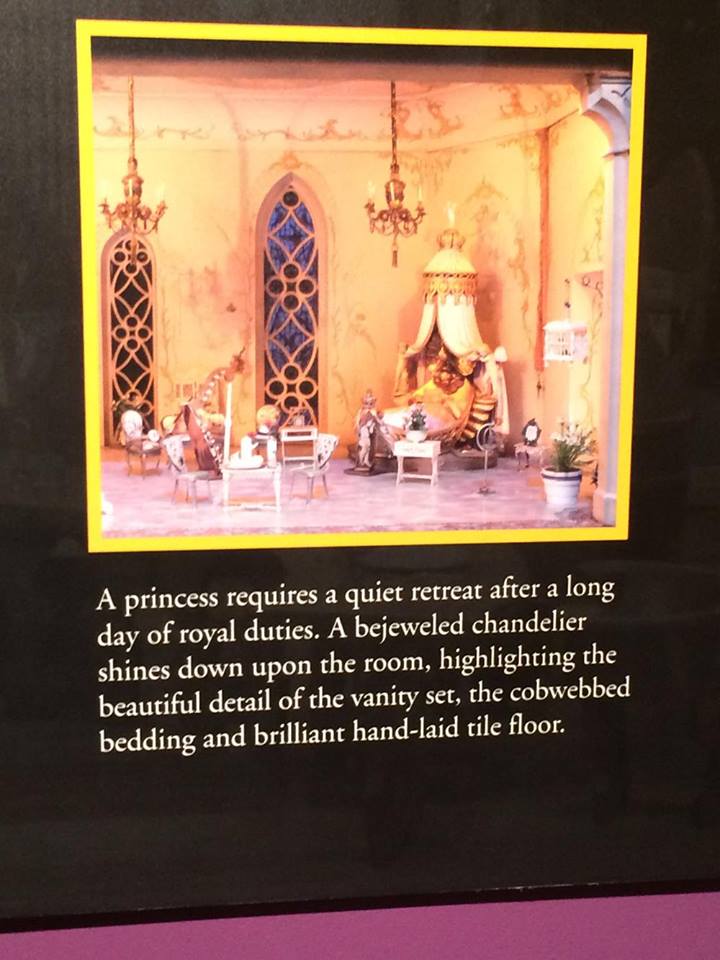

Moore’s house becomes all the more fantastic as visitors examine the upper levels. Ali Baba’s Cave boasts gems from Moore’s collection, while the nearby royal bedrooms complete the fairytale theme. There is a bedroom for the Prince, and one for the Princess, each equally ornate. The Prince’s Bedroom contains a polar bear rug, which was fashioned by a taxidermist out of ermine and the vicious teeth of a mouse. The Princess’ Bedroom houses a collection of Bristol glass, with many pieces having been contributed to Moore by strangers. The Royal Bedrooms are near the Royal Bathrooms, decorated in alabaster and diamonds. The silver spigots are functional and produce a fine stream of water. Extra furniture is situated in the Attic to avoid clutter in the main rooms.

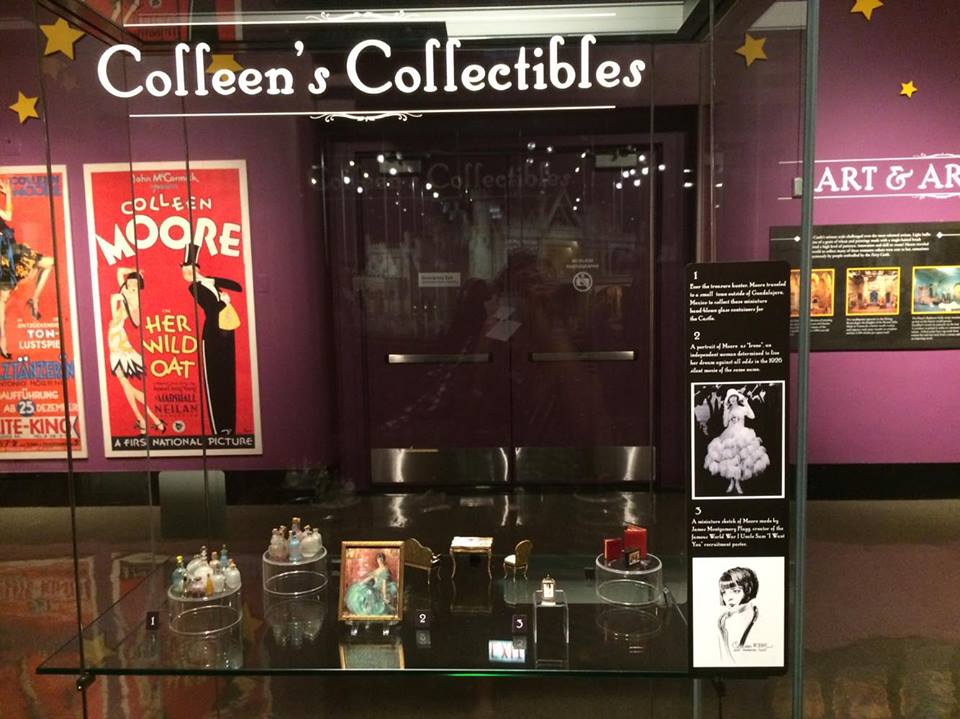

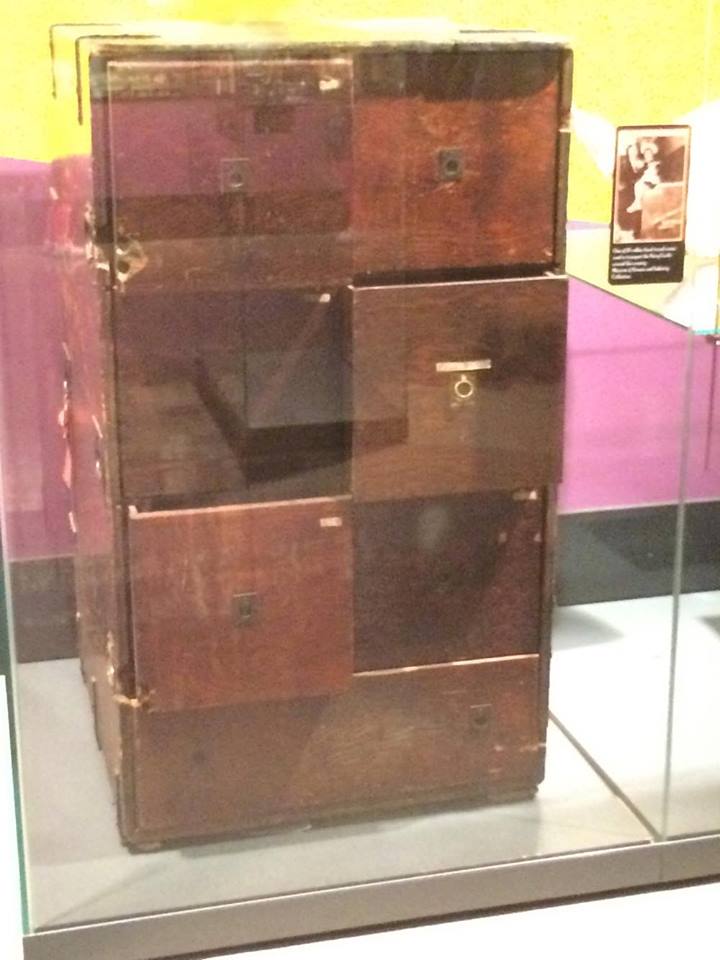

The museum displays the dollhouse in its own exhibit hall, which features additional miniature items from Moore’s collection, items used to store and transport pieces for the dollhouse, and information about her film career. The Museum of Science and Industry is located at 5700 S. DuSable Lake Shore Dr., Chicago, Illinois.

Though Moore is noted as a silent film heroine, she especially impacts young and old to this day through her Fairy Castle. The Fairy Castle is visited by a constant stream of awestruck children, and speakers in the exhibit hall share details about the dollhouse. According to the museum, it is seen by 1.5 million people annually and is worth roughly $7 million.

In 1923, Moore and McCormick resided at 1231 S. Gramercy Place., Los Angeles, California. The home remains virtually unchanged on the exterior.

In 1925, Moore and her husband lived at 530 S. Rossmore Ave., Los Angeles, California. This home also exists today.

By 1929, Moore and her husband resided on a three-acre estate at 245 Saint Pierre Rd., Los Angeles, California. The home remains today.

In 1964, Moore co-founded the Chicago International Film Festival, which is held annually to this day.

Moore has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, honoring her work in motion pictures. The star is located at 1549 Vine St., Los Angeles, California.

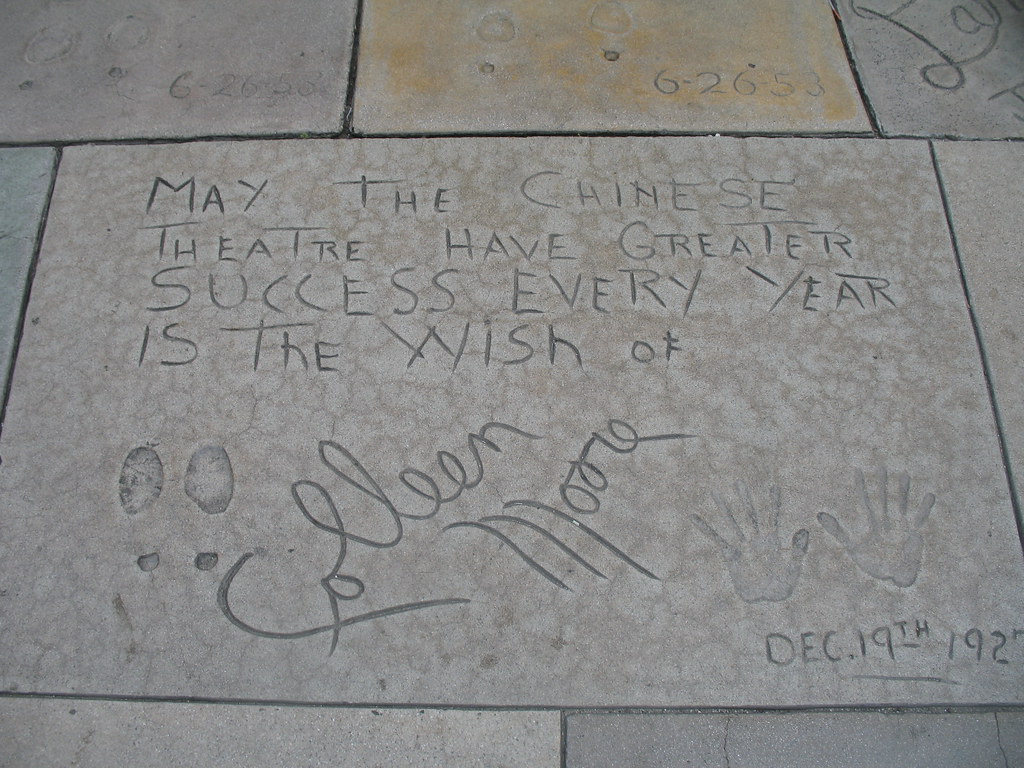

Moore’s prints can be found in the forecourt of the TCL Chinese Theatre, located at 6925 Hollywood Blvd., Hollywood, California.

Fabulous! I would love to see this in real life. I love Colleen Moore and this is such an achievement 😃 Many thanks as I didn’t know about her love of dollshouses 😊👍

A very interesting report! Thank you for sharing this.

Being a huge fan of both Colleen Moore and miniatures, I looooooooved this post! It’s definitely a bucket list goal of mine to see her “fairy castle” in person. Thanks for all the hard work you put into this article!